Call for local bloggers for a NewBizNews event

Posted on 15. Oct, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

I’m putting out a call for local bloggers within traveling distance from New York – and for journalists who’ve left their jobs or are thinking about leaving to start local news blogs – to attend a series of workshops at CUNY on Nov. 11.

The first half of the day, we’ll be presenting and discussing the New Business Models for News Project projections for the local news ecosystem (earlier presented at a Knight Foundation-sponsored event at the Aspen Institute). In the second half of the day, we will have workshops and discussions aimed at improving local sites’ businesses: setting up; serving ads; selling ads; marketing; managing communities; and more – plus presentations by companies working to help these sites, including Outside.in Growthspur, Prism, Google, Addify, PaperG, Spot.us, and others. We will have a mix of bloggers, editors, publishers, entrepreneurs, investors, and companies working in the new local news ecosystem. Gannett New Jersey and The New York Times are contributing to the effort.

Space is limited so right now we’re just putting out the call for bloggers and journalists who have or plan to have local sites to give them priority. A preemptive apology to those for whom we don’t have room; we’ll do our best to accommodate everyone we can. Know also that we’ll be streaming the day. If you’d like an invite, please email David Cohn ([email protected]), who’s kind enough to help organize this, our third CUNY conference on the topic, and who’s a helluva lot better organized than I am. Please make sure to give us a link to your site.

Continue Reading

NewBizNews on All Things Considered

Posted on 07. Oct, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

NPR media correspondent David Folkenflik came to CUNY to report on the effort to find new business models for news, including our Knight Foundation funded presentation at the Aspen Institute:

Continue Reading

The model of the new media model

Posted on 03. Oct, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

Leo Laporte, creator of This Week in Tech and the TWiT network of podcasts, spoke before the Online News Association this week and presented the very model of the new media company: small, highly targeted, serving a highly engaged public, and profitable. (Full disclosure: I am a panelist on TWiT’s This Week in Google show.)

Laporte said he charges $70 CPMs for ads. Some questioned the $12 CPM we included in our New Business Models for News, though we went with a conservative middle-ground based on the experience of existing local businesses. If we had – as we will – instead forecast a new kind of local news business – highly targeted with a highly engaged public, like TWiT’s – the CPMs and bottom lines would have been exponentially higher. The companies are still small but they are profitable. Laporte said he has costs of $350,000 a year with seven employees now but revenue of $1.5 million and that revenue is doubling annually. It will increase more as he announces new means of distribution (to the TV; he believes that podcasting is too hard for the audience).

Rather than nickel-and-diming current business assumptions, we need to have the ambition of a Laporte and build the new and better media enterprise.

(The video is after this link; it unfortunately plays automatically, so we wanted to get it off the front page).

Continue Reading

Journalism as capitalism

Posted on 02. Oct, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

The only way that journalism is going to be sustainable is if it is profitable – and out of that market relationship comes many other benefits: accountability to the public it serves; independence from funders’ agendas; growth; innovation. This is the future for journalism we envisioned in the New Business Models for News Project.

Not-for-profit, publicly and charitably supported journalism has its place in the new ecosystem of news; that’s why we included it in our models at CUNY. I think it should fill in blanks the market doesn’t fill.

But I agree with Jack Shafer at least in part that there are dangers to relying too much on not-for-profit news. He does an admirable job listing those dangers, chief among them influence by funders and their motives. Texas Tribune funder and founder John Thornton responds here. I’ll stand halfway between them: We can use and perhaps need funded journalism but we also need to be aware of the risks and must expect transparency about them.

I see another danger, though: that not-for-profit ventures will delay or even choke off for-profit, sustainable entrepreneurship in news. I would prefer to see various of the many funders who gave funds to not-for-profit endeavors – note $5 million give to a new not-for-profit entity in the Bay area – instead had invested in for-profit companies that can build companies that support and sustain themselves rather than rely on hand-outs. That is God’s work.

Mind you, I’m not coming at this from the perspective – as some might – that journalism has to be produced only by paid professionals. I have argued that we would be wise to account for the value of volunteerism and that we must find ways to reduce the marginal cost of news and new journalism to near-zero.

But in terms of saving the functions reporters perform, I think we should find ways to support them and their work in profitable enterprises. So, in a rare moment, I disagree with Clay Shirky that we must rescue reporters as charities. This call continues the notion that journalism is in a crisis. No, its legacy owners are in a crisis because they could not and would not change; Clay’s right that their models and buildings are burning. But journalism is facing no end of opportunities (as the Knight Commission’s Ted Olson said at today’s Knight Foundation presentation of the group’s recommendations: never before in journalism has there been so much opportunity for innovation in journalism).

So let’s not save those reporters and let’s certainly not save doomed companies that refused to change. Let’s invest in the future, in creating new means of gathering and sharing a community’s news that are better than old methods and that are more efficient and thus more easily sustainable. That’s what we present in the New Business Models for News. When we presented at the Aspen Institute this summer, I pointed to a blog post I wrote (but can’t find now) a year and a half ago arguing that when the Washington Post bought out reporters, it should invest in them, setting them up with blogs and businesses and promoting and selling ads for them. That resonated. And that is one step toward a new model built on networks, profitable networks. There are many more that need building.

Continue Reading

Two Paid Models for Metro News

Posted on 30. Sep, 2009 by Matthew Sollars.

The debate over paid models has grown heated in recent months as publishers cast about for new revenues to replace declining advertising dollars. But, although asking readers to pay for the news seems to have gained favor of late, publishers are still divided on whether charging for online content is the best approach. Indeed, just 51% believe it will work.

In an effort to add to the paid-content discussion, we’ve built two versions of a paid model. The first is a “pure” paid content model where 100% of the main news site sits behind a pay wall. The other is a hybrid model that envisions keeping up to 80% of the content available for free. Both models have four scenarios with varying subscriber and fee levels (the hybrid model has additional variables for the level of free content, set at 50% and 80%). As with most of our models, Jeff Mignon and Nancy Wang at Mignon Media helped us build these paid versions and provided invaluable guidance and insight throughout.

Download the full paid version here and the hybrid here.

If you’ve taken a peek at any of the other models we produced and presented to the Aspen Institute you’ll see many of the revenue and expense components are repeated here. We’ve kept our staffing assumptions roughly the same and this news organization can take advantage of some of the same revenue opportunities (like events, coupons, and a range of services to local businesses) that are open to a free metro-wide publication.

Here are a few take-aways on the paid models:

– According to our assumptions, the main site of the fully paid model loses millions throughout the 3-year period.

– In three out of four scenarios, the main site in the hybrid model is profitable in year 3 (with the B-to-C and B-to-C services, it could be profitable in year 2).

– Profitability rises along with the level of free content.

To account for the impact of a paywall on advertising, we have made some notable adjustments from our New News Organization model:

– We’ve reduced the average sponsorship revenue assumption to $100 per week from $1500.

– We also reduced the commission the organization takes on ads sold into a metro-wide ad network to 2% from the 20% estimated in the free version.

I’m guessing that some folks will take issue with a few of those assumptions. As always, we hope you will tell us where exactly we’ve gotten it wrong. Plug your own numbers into light-blue cells on the “Paid Model Options” page and then send your spreadsheet back to us. If you prefer to work in Google Docs, the full paid model is here while the hybrid model is available here. (The New Business Models for News Project has been funded by the Knight Foundation.)

Continue Reading

NewBizNews on MPR

Posted on 28. Sep, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

I joined Alan Mutter on Minnesota Public Radio this morning talking about new business models for news. Mentions of the project and the discussion at the Knight-Foundation-funded Aspen Institute presentation. Have a listen:

/**/

Continue Reading

The X Prizes for news (and media)

Posted on 25. Sep, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

A conversation with our Knight Foundation friends at Aspen inspired me to think through what an X Prize for news could accomplish. Then this week’s report in the New York Times about the awarding of the NetFlix X Prize – and the far greater value it created, not just for NetFlix, but for its participants and others – inspired me to buckle down and open that conversation here (and at my blog).

I’m not asking idly. With the right structure, I’d seek funding to administer such a prize at CUNY and we can hope that smart companies, organizations, and patrons will see that an X Prize could be a way to innovate aggressively and openly. Or is it?

We must start with a question: What is the core problem the prize is trying to solve? It can’t be just about getting more revenue for existing companies or thinking of another way to tell a story or, Lord knows, making something cool. The best expression of the problem will yield solutions that must be groundbreaking and new, quantum leaps undertaken on daring, hope, and hubris. Innovation won’t come from incremental changes to an existing structure. We know that too well.

Another key question is how success is measured – tangibly, metrically, from a distance, not emotionally. In something as amorphous as news, that’s going to be hard.

Next, we have to define news carefully – that is, broadly. News shouldn’t be defined as we do today, for the winners of the prize may create something we haven’t seen yet. Our definition of news is probably just about a community informing itself – better informed individuals and society (“better” as defined by them).

Finally, we have to recognize that the problems to solve are centered more on business issues than product issues – on sustainability – but that is not to say that the product should not be radically rethought as part of this process.

I see three key problems to solve for news (which I’ll make conveniently alliterative):

1. Engagement. In our most recent phase of the New Business Models for News at CUNY (funded by Knight), we used the sinfully low industry standard for engagement with newspaper sites: 12 pageviews per user per month. Facebook users have that much interaction with the service every day. Time spent online in social sites and blogs accounted for 17% of time overall – vs. 0.5% for newspaper sites, according to separate estimates (and advertising on social sites doubled while it plummeted for newspapers). For God’s sake, if news services were truly of their communities, they would have many times more interaction with many times more people in those communities and interaction would go far beyond reading.

Engagement is a core business problem. If you plug in higher numbers into our NewBizNews models – and we will, in our blow-out cases – you’d see much better businesses able to support much more news. You’d see news as a very profitable industry again.

So let’s say the first challenge is to multiply a community’s engagement with news. How is that to be done? Surprise me. Shock me. Invent entirely new ways, new platforms, means, and media to gather and share news.

How do we measure engagement? I would not measure by pageviews – in great part because I do not want contestants to just assume that it’s a site they’re inventing. See one more time Marissa Mayer on hyperpersonal news streams and me on hyperdistribution. News has to go where the community is and we no longer expect the community to come to it. It has to be of and among the community. Time is a slightly better measure of engagement but it, too, is shallow and can be manipulated with tricks.

No, engagement is more about ownership: people believing that and acting as if they owned this thing. It’s theirs – as Wikipedia’s and craigslist’s communities believe they own those properties and as each of us believes we own our Facebook pages or Twitter feeds or blogs. But an opposite danger lies there as well. One shouldn’t measure engagement by contribution (as many of us did in the early days of the web). Go to Wikipedia’s 1 percent rule.

So I’d say the measurement has to be made by a combination of metrics – say, time combined and attitudes: Take a baseline a survey of users of news sites today against certain beliefs – “My newspaper.com makes me part of the community of news”; “Newspaper.com is a member of my community of news just as I am”; “I feel a stake of ownership in newspaper.com”; “I feel a measure of control over newspaper.com”; “I feel a responsibility for newspaper.com”; “I am better informed with newspaper.com”. Then require that the new thing multiple some index of these factors by an impressive amount. If Facebook is 30 times more engaging than a newspaper site, then how about 10 times, even five times – that would make a huge difference in the business of news.

2. Effectiveness. This is effectiveness for media’s other customers, its paying customers: advertisers, or perhaps we should say marketers (to include ecommerce and not limit the business relationship).

News sites – like most media sites – are still selling what they used to sell in their old media: space, time, eyeballs, scarcity. Google won business away from them by selling something else: performance. Google thus takes on risk on behalf of advertisers – if Google doesn’t deliver relevance and you don’t click, it doesn’t get paid – and so its interests are now aligned with its advertisers’. And because Google created an auction marketplace that takes advantage of abundance – there is no scarcity on the internet – then prices are lower. For an advertiser, what’s not to love? That’s why I roll my eyes when old media people complain that Google stole their money. No, Google competed and saved advertisers their money.

At the same time, I believe that news and media will be supported primarily by advertising and so they had best figure out new ways to serve advertisers – even as advertising shrinks. For purposes of sustaining news, I think it’s best to concentrate on local advertising, because – in the U.S., at least – most journalistic resource is expended locally, much of government is local, there is opportunity to grow there, and the crisis in the news industry is primarily local.

The solution cannot be about increasing clickthroughs to banners. That merely extends the bullshit online media are selling. No, it has to be about much richer ways to measurably improve merchants’ businesses: to add value.

Ah, but measuring it is the tough part for that itself sets the shape of the invention: Is it more people to a web site, more people to a door, more sales of particular merchandise, better brand awareness, better relationships? Help! What do you think?

At CUNY, with additonal funding, we soon hope to do more research with local merchants for NewBizNews to get a better sense of their needs. But then again, they may not know it until they see it. I’ve spoken with advertisers who still don’t understand why a customer’s Google search matters to them.

So for the sake of discussion, let’s say that one could take a test group of merchants and used the methods and means created by a contestant to utilize a relationship with online media of some form (that is, advertising) to improve their sales by N percent over N period with at least an N return on investment. In the end, it’s simply about improving their businesses, isn’t it?

Any multiple of this effectiveness would also have a profound impact on the sustainability and profitability of news (so long as it’s a news entity that makes it possible). In our New Business Models for News, we used what we believed – though some disagree – was a conservative $12 CPM ad rate. It was also conservative to presume old ad models: i.e., banners. But then Google’s Marissa Mayer turned around and talked about hyperpersonal news streams, emphasizing the business potential: If you know that much about people to be hyperpersonal and if you are incredible good at targeting – at discerning intent and delivering relevance – then the efficiency, effectiveness, and value of marketing there would skyrocket. An X Prize winner would think this way.

3. Efficiency. This is to say cost. What does it cost to produce news, to gather and share what a community knows? The closer that marginal cost can be brought to zero, the more news we can afford. That’s good for society.

That may not sound good for professional journalists, I know. And employment of journalists has been the default measurement of the health of news. (This is why I have quibbled with BusinessWeek’s Michael Mandel’s analysis, here and here.) But I’m not suggesting that there are necessarily fewer reporters (there will be fewer production people). Indeed, in our New Business Models for News, we ended up with a equivalent number of people doing journalism in our hypothetical market, only they weren’t all in a single newsroom. Most worked in entrepreneurial ventures that many of them owned, and they as a group devoted far more of their time to reporting. The net result, we believe is more journalism because it is more efficient journalism.

So I’m suggesting that journalists be made as efficient as possible and the way to do that is to make them highly collaborative and to take advantage of the work people are willing to do just because they care – the hundreds of millions of dollars people contribute to Wikipedia, adding value to it and making it both supremely efficient and incredibly valuable.

So I suggest this prize start with the goal of maximizing the journalism, finding the best ways to get the most relevant news to the most people at the lowest cost: the best way to make the most people feel well-informed from a sustainable venture. Once again, we must be cautious about the definition of news, not limiting it to the broccoli served cold currently. What do people want to know and need to know and how can we get that? What is the news that isn’t shared that has to be reported and investigated and why and how do we get that? So I might start by finding communities and having them define news and what it means to be informed, what they need to run themselves. Of course, we also need to define quality. This needs to be reliable and useful information.

How do you make a measurable contest out of that? I’m not sure. Perhaps we find a community and find out how many people want to know about, say, their school board and town board and tow events and then measure what they want to know now. Then the winners made their community better informed by the greatest margin at the lowest cost while still not losing money.

In the end, if we can find new and daring solutions to these problems of engagement (formerly known as audience), effectiveness (advertising), and efficiency (operations), we can improve news as a product (and process), its relationship with its public, its value to its customers, and its sustainability. That’s the goal. It’s going to take new thinking and experimentation to get there. An X Prize is one way to get that.

What do you think?

Continue Reading

Counting on Membership, Redrawing our Not-for-Profit Model

Posted on 23. Sep, 2009 by Matthew Sollars.

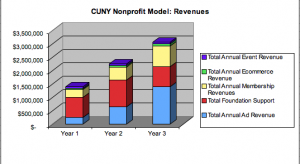

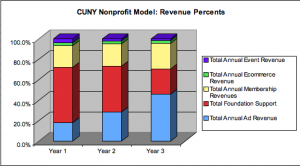

We’ve heard a fair bit of criticism in recent weeks that the revenue estimates (mostly in advertising) in some of our for-profit models were far too high. So, we are surprised to hear from Jim Barnett that the membership projections in our not-for-profit model are too low.

By his lights, a not-for-profit like the one we envision (not unlike the real-life MinnPost), could reasonably generate more than $700,000 in membership revenues by year three, compared to the $547,000 we had estimated. Barnett, a journalist who is studying not-for-profit management at The George Washington University, was kind enough to plug his own assumptions into our model. His revision is available as an Excel download here.

By his lights, a not-for-profit like the one we envision (not unlike the real-life MinnPost), could reasonably generate more than $700,000 in membership revenues by year three, compared to the $547,000 we had estimated. Barnett, a journalist who is studying not-for-profit management at The George Washington University, was kind enough to plug his own assumptions into our model. His revision is available as an Excel download here.

Barnett started with a slightly higher number of member-donors in year one, taking the number of MinnPost members in its first 14 months and translating that to cover just 12 months. His calculations include some members not included in MinnPosts’s annual report (which was our source), arriving at a first year membership estimate of $298,000, roughly $25,000 more than our model.

But the real differences start to show up in years two and three as the news organization matures and puts roots deep into the community. Barnett estimates that by year three the not-for-profit should aim for a five-fold increase in the total number of members, to 4,157 from 762.

But the real differences start to show up in years two and three as the news organization matures and puts roots deep into the community. Barnett estimates that by year three the not-for-profit should aim for a five-fold increase in the total number of members, to 4,157 from 762.

Barnett, who is studying not-for-profit management at George Washington University, says his assumptions draw on studies of membership efforts at mature not-for-profits. Typically, a robust membership drive will result in a pyramid where the majority of donors are at the lower contribution levels. Rather than extrapolating membership based on a conversion of estimated unique visitors (as in our model), Barnett has drawn a picture of what a healthy membership pyramid for a metropolitan news organization should look like in three years. Even with his more robust assumptions, however, Barnett’s organization still converts just one percent of estimated unique visitors. Indeed, the lowest rung accounts for much of the growth in Barnett’s model while membership at higher levels grows more slowly and actually decreases in the highest.

While there isn’t a defined statistical correlation between the top and bottom of the pyramid, Barnett says there is a relationship.

“It’s a social process, people see what leaders in the community and their peers are giving and say they want to be a part of that,” Barnett says. “People start small and work their way up. Not every body will move up the ladder, not everybody who moves up will go to the top, but the end game as a not-for-profit is to make this a part of people’s lives. When there’s a socialization to it, that’s when you start getting the reinforcing numbers at the lower end.”

More and more journalists, casting about for ways to preserve their livelihood, have been drawn to the not-for-profit model. The Voice of San Diego announced last week that it will provide advice and support to an offshoot in nearby Orange County and Spot.Us has launched a franchise in Los Angeles. But, as Barnett makes clear in a post on ProPublica’s effort to start finding alternatives to foundation grants, launching a not-for-profit cannot be a “tin-cup substitute” for journalists who balk at running a business.

“A lot of these organizations get the grant money but then struggle to make it on their own, he says. “That’s what this is about, how to go from being hatched to going out in the wild to survive.”

Want to add your own assumptions to our models? Go right ahead! And, please, shoot them back to us. (The New Business Models for News Project has been funded by the Knight Foundation.)

Continue Reading

Did we ever pay for content?

Posted on 19. Sep, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

In an essay that, on first blush, ranks near to Clay Shirky’s seminal thinking-the-unthinkable think piece, Paul Graham argues that we never paid for content:

In fact consumers never really were paying for content, and publishers weren’t really selling it either. If the content was what they were selling, why has the price of books or music or movies always depended mostly on the format? Why didn’t better content cost more?

A copy of Time costs $5 for 58 pages, or 8.6 cents a page. The Economist costs $7 for 86 pages, or 8.1 cents a page. Better journalism is actually slightly cheaper.

Almost every form of publishing has been organized as if the medium was what they were selling, and the content was irrelevant. Book publishers, for example, set prices based on the cost of producing and distributing books. They treat the words printed in the book the same way a textile manufacturer treats the patterns printed on its fabrics.

Information – Bloomberg terminals, stock newsletters – is a different business. Publishers flatter themselves when they argue they are in it.

What happens to publishing if you can’t sell content? You have two choices: give it away and make money from it indirectly, or find ways to embody it in things people will pay for.

The first is probably the future of most current media. Give music away and make money from concerts and t-shirts. Publish articles for free and make money from one of a dozen permutations of advertising. Both publishers and investors are down on advertising at the moment, but it has more potential than they realize.

I’m not claiming that potential will be realized by the existing players. The optimal ways to make money from the written word probably require different words written by different people….

The reason I’ve been writing about existing forms is that I don’t know what new forms will appear. But though I can’t predict specific winners, I can offer a recipe for recognizing them. When you see something that’s taking advantage of new technology to give people something they want that they couldn’t have before, you’re probably looking at a winner. And when you see something that’s merely reacting to new technology in an attempt to preserve some existing source of revenue, you’re probably looking at a loser.

Continue Reading

Is journalism an industry?

Posted on 18. Sep, 2009 by Jeff Jarvis.

Journalism is a business – that is how it is going to sustain itself; that is a key precept of the New Business Models for News Project, funded by the Knight Foundation. But is it still an industry dominated by companies and employment?

In the first part of his analysis of the news business, BusinessWeek chief economist Michael Mandel equates bad news about news with the number of journalists employed. He charts newspaper jobs falling from more than 450,000 in 1990 to fewer than 300,000 today and calls that depressing – which it is, if one of those lost jobs is yours. But it could also signal new efficiency and productivity, no? Looking at these numbers with the cold eye of an economist whose magazine and job aren’t on the block, perhaps it is nothing more than the path of an industry in restructuring. Perhaps it’s actually a signal of opportunity. Indeed, Mandel then laid that chart atop one for the loss of jobs in manufacturing and found them sinking in parallel, with newspapers just a bit ahead on the downward slope today. “Not good news, by any means,” he decreed.

But there is the nub of a much bigger trend: the fall news as an industry paralleling the end of the industrial economy. That’s not just about shedding the means of production and distribution now that they are cost burdens rather than barriers to entry. It’s about the decentralization of journalism as an industrial complex, about news no longer being based solely on employment.

A few months ago, I quibbled with Mandel’s BW cover story arguing that America has experienced an “innovation shortfall.” There, as here, I think he’s measuring the wrong economy: the old, centralized, big economy. In both cases, he misses new value elsewhere in the small economy of entrepreneurs and the noneconomy of volunteers.

I return again to the NewBizNews Project, where we modeled a sustainable economy of news at between 10-15% of a metro paper’s revenue – about as much as any of them bring online – with an equivalent amount of editorial staffing but those people are no longer all sitting under one roof; they work in – and oftentimes own – more than 100 separate enterprises. I return, too, to the Wikimedia Foundation calculating the value of time spent on edits alone with it adding up to hundreds of millions of dollars.

In both cases, tremendous value is created at tremendous efficiency outside of the company and in great measure outside of employment.

So is employment the measure of news? No. Is it the proper measure for every industry? Not necessarily. Is it the measure of the economy? Not as much as it used to be. Media is becoming the first major post-industry. Others will follow. You just have to know where to look.

* * *

It’s one matter when new value is created outside old companies in industries such as retail – in WWGD?, I cited $59.4 billion in sales from 547,000 merchants on eBay in 2007 vs. $26.3 billion in 853 Macy’s stores – but another matter when the employment is replaced in industries built around priesthoods: journalism, education, even government and medicine. Then not just economics but behaviors change.

Thus we see fretting about a “post-journalistic age” when new people perform some of the tasks journalism employees used to perform, whether that is advocates digging dirt or universities reporting their own scientific advances or sports teams funding their own reporting or volunteers organizing to report collaboratively. These are just a few of the latest examples from my pre-surgery tabs about voids being filled in new ways by new parties with new efficiencies. This is another reason it’s dangerous to calculate journalism’s size according to journalism’s jobs.